Steering the Craft: A Twenty-First Century Guide to Sailing the Sea of Story by Ursula K. Le Guin | Review

Publication: Boston ; New York : Mariner Books, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2015

Genre: Authorship, Narrative Writing

Pages: 141

Formats: Paperback, eBook

Source: MCL

Let’s talk about writing exercises. Le Guin packs this modest-sized book full of lunges, squats, and sometimes gut-wrenching sit-ups all the way through. As a result, you’ll want your favourite writing tools nearby while diving into this one. But it’s not exercising because it’s the fashionable thing to do or because you don’t have any of your own writing topics to play with.

Le Guin states in the book’s opening lines that she composed this “handbook for storytellers — writers of narrative prose.” She further explains in her introduction that the book is for those who know how to write at least competently, and perhaps even rather well, but who also want to hone their talents around the more technical waters that can often throw even a great writer somewhat off course. When we write, we want to be heard, and to be heard is to be understood. Writing is our medium toward spiritual (the term being used generally, rather than with religious specificity) connection. To connect with another sentient being is to strive towards clarity, and not even clarity in the puritanical sense, but simply as a meeting of all the elusive mind-and-emotive-stuff we couldn’t otherwise hope to express.

It’s no pun that Le Guin uses the word craft in her book’s title, because writing is just that. Because just like the products of a master musician or painter, we’d expect the finished pièce de résistance to be the result of years of practice. And who knows? Maybe you’ll get a few usable story-gems out of the writing exercises she gives at the end of each chapter. But please don’t be surprised if many revisions prove needed after each painstaking draft. As mentioned, this is a book to help aspiring writers stretch and practice the artistry that is prose writing. Failing at any endeavor is part of the comparable success story in the end.

If you’re truly going to approach your writing with the concentration of a master, Steering the Craft is a wizard-of-word’s spell book detailing the “practice in control” of bending “the pleasure of writing, of playing the real, great word games” toward usable production. Understanding how to use point of view, verb tenses, short and terse versus long and wandering sentences, as well as the benefits of extricating all those pesky adjectives is how the game is played. (Yes, I’m wringing my hands that “pesky” snuck into that last sentence.) This book provides a sandbox for aspiring writers to root around safely, the only ramifications being to gain a more objective view of their world-building efforts.

Le Guin left such a legacy of word-spun anthro-fiction in her much-missed wake for many of us, and we still have much to learn from her generous advice on the art form she knew best.

Just a quick note: I love that the original version of this book, published in 1998, had the subtitle of “Exercises and Discussions on Story Writing for the Lone Mariner and the Mutinous Crew.” Lots to pull out of that one.

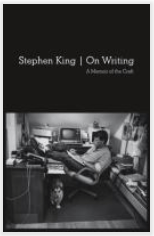

On Writing: A Memoir of the Craft by Stephen King | Review

Publication: New York: Scribner, 2000 | Republished in 2010, 10th Anniversary Edition

Genre: Authorship, Narrative Writing, Memoir

Pages: 288

Formats: Paperback, eBook, Audiobook

Source: MCL

I can’t spout enough praise for this one. King gives not only the most humorous advice about the tireless (and more often exhausting) work each writer puts him or herself through, he also offers a memoiristic curriculum vitae to inspire (or perhaps frighten) other writer-wannabes. After the first section of his book opens the blinds of his youth, filled with farting babysitters and countless rejection letters that he pins to his teenage bedroom wall with pride, King gets down to the business of explaining the business of writing.

While we may all want to skip straight to the last section of the book, which details his surviving a van that misplaced its heaving mass into his person while he was walking on the roadside in 2000 (no, the experience wasn’t his inspiration for Misery, which he actually wrote back in 1987, closer to the beginning of his now well-publicized career), the bits of the book I found most inspiring were those focused on his honest assessment of what being a writer takes in the long run.

The surprising answer to this enduring question we who are just beginning the writer’s journey can’t seem to get out of our heads is that the secret to becoming a writer is, quite simply, to write.

King is maybe somewhat harsh in his estimation that bad writers will never improve, and that great writers are born and not made, yet he seems to have a fondness for helping competent writers blossom into good writers. So, there’s hope! Maybe. But who is ever going to tell a bad writer that they’re prose stinks? I’ve never had a composition teacher dare utter such a judgement, but maybe that’s just due to our overly sensitive and politically-steroided culture. I’ve had writing teachers beg me to be on the school newspaper staff or to take up positions as a writing mentor, but the former scared the shit out of me because talking face-to-face with strangers sounds like torture, although I endured with some ecstasy the latter for a couple years in college.

What’s the line between bad and competency when we’re talking about writers? Incompetent writing (to me this equates to bad writing, and maybe King would agree) seems to imply you just don’t understand how to effectively expose your thoughts to an absentee audience, grammar eludes you, and organization is certainly not your forte; but mostly the first of these three. As if you need the crutch of hand gestures and facial expressions to help your actual words get your point across the chasm of understanding. Writing doesn’t allow for visual crutches, as we know all too well from the magical chaos that can destroy relationships and even governments in our world of text messages, email, and Twitter (America has a prime example of this last one at the moment, and if that statement baffles you, well god bless ya for having successfully hidden your head in the sand for the last 24 months). A good writer, according to what I’ve gleaned from King’s book, seems to be someone who is both competent at the composition of written communication and an artistic weaver of tales.

King’s book deals exclusively with writing fiction, but if we’re going to expand his assessment of writing skills to formats such as essays, memoirs, and historical investigative journalism, then I’d say the story weaving criteria still holds true. An essay is a story that follows the meandering yet formulaic thoughts of the writer, thinking specifically of Virginia Wolf’s expanded book-sized essay A Room of One’s Own or Ursula K. Le Guin’s collection Words Are My Matter. As far as historical investigative journalism goes, while The Lost City of Z made for an okay movie version of the historical events it recounted, I’d argue for skipping the televised rendition and just plunging straight into the pages to consume the (here it is again) story just as it was originally laid out by the book’s author. And then we have memoirs like Augusten Burroughs’s Running With Scissors and Kate Chirstensen’s Blue Plate Special, which are themed glimpses into the writers’ lives where the chorus of events are carefully orchestrated until the scenes virtually sing in the readers’ minds.

King also spends time waxing philosophical in his advice to ambitious writers to also read read read. How can you know what’s good, or bad, if you’re locked in a vacuum? Maybe you too wanna write a memoir about all the crazy terrifying things you’ve faced in your short life (even if you’re 107, it’s still relatively short in the grand scheme of our universe’s history, mind you). The best place to start is in front of the autobiography section of your local library or bookstore, baby. As Jo Walton has pointed out, “We all remake our genre every time we write it. But we’re building on what’s gone before.” (https://www.tor.com/2018/01/24/bright-the-hawks-flight-in-the-empty-sky-ursula-k-le-guin/#more-331580) Even the greats of the writing world had influences. And, as a result, even the most individualistic writer’s voice is the product of a literary stew.

The takeaways from King’s book on writing? Write and read like your life depends on it. Guard time for both as you would a scrap of driftwood in a storm-torn sea.

A friendly note to the reader who prefers listening: The audiobook for King’s book does not include the postscript that gives a visual example of what should happen to a first draft after it’s rendered subject to the writer’s critical pen of edits and, hopefully, improvements. Just thought you should know. Nor does it include the two additional postscripts (the second was tacked on in the 2010 republication edition) listing what King was reading while writing On Writing. Just a friendly heads-up. If you’re serious about your writing, get the print version and keep it handy next time you’re sweating over that manuscript that’s been kicking your ass.

Note: Yes, I know some of the words above are made-up. Agatha asks that you kindly engage your sense of humor and imagination. It’s more fun that way.